When magnified film image reveals its grain structure. The grains have the form of irregular dark stains, often combined in clusters.

Nearly all monochrome emulsions used for film purposes share a similar chemical composition, including the gelatine-suspended crystal hexagonal grains of silver bromide.

Emulsion consists of: ca. 75% of gelatine, 24% of silver bromide, from 0.5% to 1% silver iodide, vestigial quantity of potassium bromide and water. The visible differences between negative and positive films consist in the application of varied concentrations, temperatures and time of the “maturation” of emulsion.

PRODUCTION OF PHOTOSENSITIVE EMULSION

As a heterogenous set, photographic emulsion contains fine-crystalline halides of silver in gelatine. Production consisted in a mutual exchange of ions of silver nitrate AgNO3 and potassium bromide KBr in water solution.

AgNO3 + KBr -> AgBr + KNO3

The proper process of production of potassium bromide consisted in merging ions of silver with ions of bromine, as a result of which a difficultly soluble silver bromide came into being, precipitating in the form of yellow sediment.

Ag + Br -> AgBr

If the solution contained gelatine, the result was not sediment but a suspension of microscopic fine crystals of silver bromide. Together with its suspension, silver bromide created a highly photosensitive emulsion. The degree of photosensitivity of the emulsion depended on the size of silver bromide grains in the suspension, and on the kind of gelatine. Gelatine contained a range of products of the decomposition of organic material (animal) from which it had been acquired, and these substances had the ability of increasing photosensitivity of silver bromide under the condition that it was heated with it in moderate temperature. This is what the so-called maturation of emulsion consisted in, during which silver bromide was subject to physical changes, i.e. increase in the size of grains and physical changes under the influence of the admixture of gelatine. The sensitivity of emulsion increased up to a certain maximum, after which it began to turn grey and the so-called fogging effect occurred. Achieving high photosensitivity was extremely difficult. It required not only appropriate temperature and heating time, but also the proper kind of gelatine.

|

|

microscopic image of the grains of photographic emulsion from: http://www.kodak.com/US/en/corp/researchDevelopment/whatWeDo/technology/chemistry/silver.shtml |

The problem of the size of the grain of the image concerns mainly 35mm photography and film. The history of fine-grained development began in 1904 with Lumière and Seyewetz. According to their observations, some substances used for development, like para-phenylenediamine and orto-aminophenol gave finer grain than other developers. The use of new solutions provided for a clearer image and reduced the distortions of the played sound.

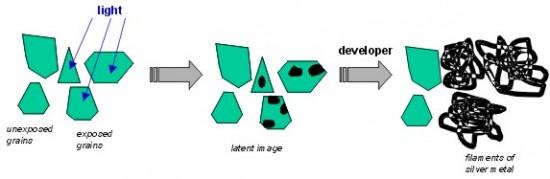

The surface of grains features points that contain small clusters (the so-called nuggets) of metallic silver and silver sulphide, which come into being during the maturation of emulsion by seizing the atoms of silver released in the process. Under the influence of the reducing effect of the developer, the nuggets grow at the expense of the grain, which “germinates” in a way, sending out the edgings of metallic silver. If the developer is active for long enough, virtually entire grains change into a tangle of edgings, preserving their former shape, slightly increased. It is the so-called grain of the image. It is often the case that such “sponge-like” structures form clusters. However, if the developer acts relatively slowly and its action is interrupted early enough, silver edgings don’t absorb the entire grain and after fixing they remain in the form of smaller single grains.

|