From the very onset of cinematography, the unnatural greyness of film was in for criticism. Already in 1896 Maxim Gorky wrote about Lumière brothers’ films:

„Everything there – ground, trees, people, wateer and air is immersed in monotonous greyness. Grey sunrays across a grey sky, grey eyes of grey faces and tree leaves grey like ash. This is not life, but only its shadow.”

|

||

|

Hand-coloured film |

The untamed passion related to the will of acquiring colours on cinema screens led to the emergence of hundreds of colouring techniques. It is estimated that already in the 1920s ca. 80% of film copies were colour. The development of techniques was subjugated to film production, exposure, developing, or even distribution. Thus, e.g the moment sound was introduced, manual film colouring was rendered more difficult due to inconvenient editing.

The hues of most of coloured films have been irretrievably lost. The moment a safe carrier appeared on the scene, films made on highly inflammable base were mass copied onto black and white ACETATE film. For safety reasons, original materials were destroyed together with the memory of their genuine colour.

Already in 1918 William Kelly introduced the division into coloured films and natural colour films. The difference pertained not only to the manufacturing technique, but was also related to issues of aesthetic nature. Coloured films, hand-painted or made with a stencil were most often coloured after the exposure of the film. These processes were targeted at fantastic, sometimes surreal plots devoted to remote exotic lands that were real or existed only in the artists’ imagination. Natural colour films were based on the technology of the film stock with a special emulsion that usually consisted of three layers, whose record reflected all colour gradients that human eye can see. The films were reserved for documentaries of the epoch or films set in the present day. Thus it was Paris that came to be the capital of coloured film, mainly with the activity of the company Pathé, whereas natural colour films hail from Great Britain and the USA.

COLOURED FILMS

COLOURED FILMS

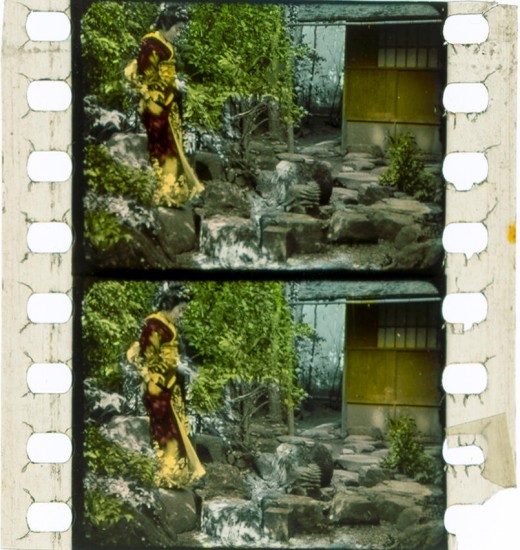

It is difficult to disagree with Paolo Cherchi Usai, who compares hand-coloured films to medieval miniatures, not only because of their size (dimensions of the frame), but also because of their mystical atmosphere. The film “trompe l’oeil” created the illusion of a three-dimensional image, but primarily took the viewers into the land of beautiful, purely illusionary colours.

It is said that the first manually coloured film is Annabelle Butterfly Dance from 1894. It is merely one shot lasting for several dozens of seconds. It is worth remembering that at the time films were screened at the speed of 16 frames a second, and the work on colouring one fragment lasted for several months.

The most popular “plot” motif used in manually coloured films was the so-called serpentine dance. Protagonists spun in loose cloaks, which owing to sweeping movements of the arms caused the drapery to spin – ideal background for refined colour effects.

Manual colouring was carried out by means of half-transparent inks or glazing paints based on non-organic dyes. Colour was applied from the side of the emulsion, due to which gelatine could easily absorb dyes based on water or spirit. Manually coloured films faded less often. Application of paint was subject to a major improvement when magnifying glasses with heavy zoom and extremely precise paintbrushes appeared on the scene. We can imagine how much attention and time it took to apply point inside the outlines of people or objects the size of rice grain.

The basic fault of the technique was its uniqueness. Each frame was exceptional, characterised by a different amount of dye and different application of paint, therefore the unwanted effect of shape deformation appeared on the cinema screens.

Due to the cost and time that colouring consumed, very soon more effective solutions were introduced. Films became increasingly long, which simply made time-consuming operations impractical. In spite of the introduction of new solutions, manual colouring of film is carried out until the present day.

SZABLON

|

||

| Film coloured with a stencil. From: http://www.brianpritchard.com/Tinting.htm |

Due to the dynamic development of photography, there was an increasing need for giving film production a boost. In order to raise efficiency and reduce the time of work, films began to be coloured with a stencil at the end of the 19th century.

Stencil is the first technique to achieve spectacular commercial success in the film industry, apart from only the United States, where it did not prove popular. It flourished thanks to the work of Western European producers. The most important role in the development of the technique was played by the French company Pathé, which was the first in 1905 to announce the patent for the new technology by Melies and Gaumont.

Flims coloured with a stencil tackled distinct subjects. These were mainly historical works devoted to exotic trips or related to the sphere of fantasy.

The technique consisted in cutting out with a scalpel fragments of film frames for colouring. With a cut out stencil held to a black and white film copy, a brush or a tampon was used to apply watercolour paints, most often produced with aniline pigments. It made things considerably more convenient and reduced image flickering, often to be seen especially with films coloured “by hand”. It also led to colour uniformisation of the entire copy of one film.

|

| Phases of colouring with a stencil. Image from “The History of Movie Photography” by Brian Coe. |

Dynamic growth of the company Pathé led to a total domination of the market of “illusionary” coloured films by the French. Due to very developed infrastructure, Pathé did not have any important competitors. Colouring with a stencil required hiring a crowd of employees. In 1906, there were 600 women working at Pathé factories.

|

|

Female workers of the company Pathé colouring films. Image from “Moving Pictures: How They Are Made and Worked”. |

Constant improvement in stencil colouring led to a considerable mechanisation of the process. 1908 marked the creation of a special colouring system Pathechrome, based on pantograph, whose operation was incredibly precise.

The technique enjoyed the greatest popularity in the 1920s. Stencil colouring was often combined with other techniques, e.g. monochrome colouring of the entire surface of the film (tinting).

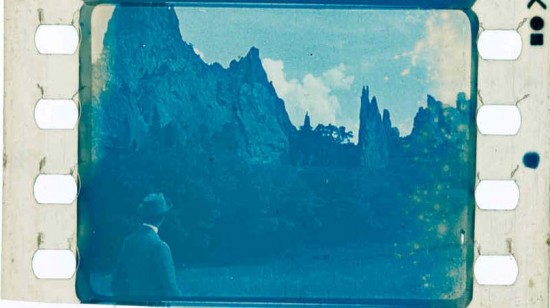

TONING

Toning (French: virage) did not gain as many partisans and propagators as the below described tinting. It was related mainly to mechanical difficulties – the need for carrying out numerous chemical baths in order to fix the colour.

|

| From: http://www.brianpritchard.com/Tinting.htm. |

Toning was based on the method of colouring the film emulsion based on a chemical transformation of parts of silver compounds into colour non-organic compounds of salts of metal. Due to the use of compounds of metal, the process was sometimes called metallic toning. The following were used for toning, among others:

• iron ferrocyanide (III), which gave colour Prussian blue,

• copper ferrocyanide, which gave colour red,

• uranyl ferrocyanide – reddish brown,

• vanadium ferrocyanide (vanadium oxide) – yellow-green,

• iron sulfide ferrocyanide – warm brown.

Toning is easy to identify, characterised by a non-coloured surface of the film stock deprived of exposed particles of compounds of silver, most often in the area of perforation. Marking of the metal suffices to identify the type of toning. Toning is a less stable process, mainly because of the impact of decomposition of nitrocellulose on the compounds of metal and the effect of UV rays from the lamps of the projector. In order to boost the toning effect, attempts were made at eliminating the excess of the compounds of silver, which did not react with other metals. With this view, since the 1920s special baths on the basis of sodium thiosulfate, causing a rapid “whitening” effect.

Film could be toned two times. Most often it was a composition of blue and pink colour.

TINTING

From the beginning of the 1920s, monochrome colouring of the entire surface of the film was one of the most popular colouring methods. Initially, dyes were applied manually, e.g with paintbrushes, tampons and rolls, but very soon the process was entirely mechanised.

One of the first manners of monochrome film colouring consisted in the use of colour varnishes and lacquers. The process was most often carried out from the side of the base by applying varnish with spray or paintbrush. One of the characteristics of this technique was that film was covered only between perforation tracks so that the edges remained colourless.

Another very popular way consisted in the use of dyes that dissolved in water. Film was immersed in a special solution until the desired effect was reached. Specific hues corresponded to single scenes or takes of the film. Monochrome coloured stocks reduced the image contrast, therefore it was recommended that copies to be coloured should have it “in reserve”. The main fault of the process was unequal colour saturation, discernible by the human eye, dependent on the time of bathing the film in the colouring solution and the force of its action. Up to nine hues were used in one film copy.

Cud nad Wisłą, fot. Monika Supruniuk

The most recognition was enjoyed by industrially coloured films produced since 1910. The raw material was meant for direct exposure of the film. Eastman Kodak offered in its catalogues films in nine colours: red, pink, orange, amber, bright amber, yellow, green, blue and lavender. In the 1920s production reached such volume that colour and monochrome films did not differ in price. The hues used in this case had to be insensitive to chemical solutions of laboratory processing. Films did not pose problems during duplication, and their colour was much more stable and resistant to the light of the projector. The list of hues used in the process could sometimes amount even to one hundred. The moment sound film appeared on the scene (in the 1920s), it was impossible to use the prior range of colours without causing distortions. Colouring seemed to be doomed to end. The effort of “reanimation” of the process of monbochrome colouring was undertaken by the company Eastman Kodak, which produced special film stocks called Eastman Sonochrome Tinted Positive Films, which did not however gain broad recognition. Monochrome coloured films were usually very dark. It was related to the absorption of colour by the light of the projector (from 25% to 95%). Watching such films was inconvenient as they caused fatigue to the human eye. If the colour was relatively weak, the viewers stopped discerning it after several minutes. This relation was known from the very onset of film production, which is proved by strong hues of long scenes and unsaturated hues of short scenes.

Specific hues were assigned to specific moods of the scenes. Amber, sepia and yellow were reserved for scenes in daylight, and red for dynamic action. Blue-green reflected mystery or showed a landscape by the sea, conventionally blue stood for the night.

The main reason to cease the production of monochrome coloured films was the introduction of the sound cinema. Production of a sound film did not assume merging a film from fragments of stock. The entire copy was exposed “in the course” to avoid even the slightest breaks in the soundtrack, which could cause crackling during screening. In turn, the system of monochrome colouring of film was based on gluing scenes and takes of various colour into a ready print. Yet, it was not the only reason for the end of “illusionary” coloured films. It was the taste of the audience that had the largest impact on pushing them out of circulation.